Up close and (too) personal with my Mitsubishi Pajero Evolution

When I drove down to the Port of Los Angeles to pick up the 1997 Mitsubishi Pajero Evolution that I had won at an auction in Japan just four months prior, only a teensy little bit of drama ensued. I expected a dead battery after such a long post-auction waiting period plus weeks on a ro-ro ship, but when a jump pack couldn’t even spark the engine to life, two good samaritans with two different trucks and two sets of jumper cables needed to come to my rescue.

Such is the power of the enthusiast automotive industry, and I chuckled to myself as I sat powerless, occasionally pumping the throttle while surrounded by an expansive parking lot chock-full of (presumably also dead) JDM icons. That rescue attempt proved short-lived, though. After the Pajero’s engine finally cranked over, all of a sudden, a searching idle and lurching acceleration cropped up as I headed for the customs shed to sign some final forms on the dotted line. The truck died twice more throughout those few hundred yards before I nearly wheeled up onto a flatbed trailer. I already felt grateful for the Dakar-developed suspension, to say the least.

[Button id=”409″]

Bringing this old dog home

A dead battery. Gnarly noises from the engine and transmission. Maybe a dry gas tank. On the long drive home, my mind raced along at breakneck paranoiac pace, wondering what I’d gotten myself into.

Back home, I poured in a few gallons of 91 octane and then checked the automatic transmission fluid dipstick—yep, those exist—only to discover the transmission pan even drier than the fuel tank. Four or five quarts of Mitsubishi Diaqueen SPIII later, I went for a test drive. The engine finally revved happily, and the gearbox shifted smoothly until I switched off the ignition again and hopped out, only to audibly hear fluid flowing out, piddling onto the concrete slab. Oh boy.

Hey, on the bright side, all the mechanical drama gave me an excuse to skip the 405 freeway as my first right-hand-drive experience in the United States. But this first day owning a homologation special went rougher than expected, nonetheless. And that’s considering how many sleepless nights I spent preparing for every last eventuality that might possibly emerge while picking up a rare car with 237,000 kilometers on the odometer and a laundry list of even rarer parts that are almost impossible to find in Japan, let alone the United States. Luckily, the Pajero Evo also shares many parts with Gen 2 and Gen 3 Mitsubishi Monteros sold here in America, and I quickly installed a Montero oil cooler line to replace the burst piece on the PajEvo.

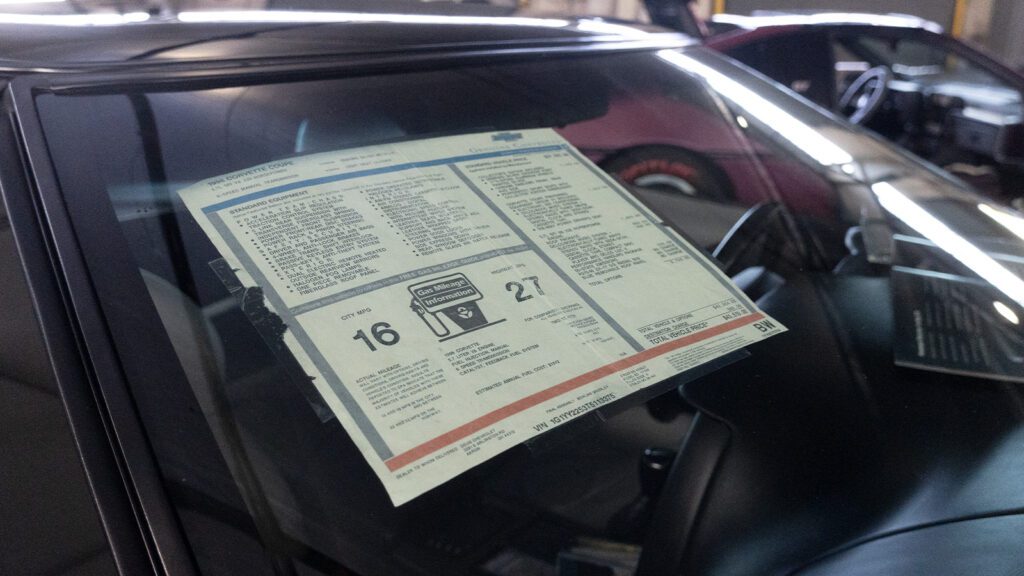

Happily ever after, at least until I used Google Lens to translate the sticker on the timing belt cover, which seemed to suggest the last timing belt job had been completed in ‘22—next, I realized that in Japan, that “22” meant the twenty-second year of the previous emperor’s reign, or 2012 by my math. So the Evo sat for a couple more months while I sourced a timing belt, water pump, and various other “while you’re in there” parts from Japan, Dubai, and, somewhat surprisingly, Rock Auto. With the truck finally running at full gas—knock on wood, I know—seemingly everyone who knows anything about anything wants to learn more about this rare Dakar racecar for the road, especially since its recent uprising in Hagerty prestige. So buckle up, kiddos. Let’s talk about the Mitsubishi Pajero’s Evolution.

A totally different beast

Pictures of Pajero Evos online only tell part of the story. Yes, those hilarious fender flares and Bat-manga-ear vertical stabilizers look awesome on a short-wheelbase truck, but beneath the skin lurk miracles that Mitsubishi’s engineers worked over to produce the Dakar Rally’s winningest vehicle ever (though Can-Am believes the Maverick X3 might soon be able to take the record by managing similar miracles, perhaps).

The biggest difference between a Pajero Evolution and the utilitarian, almost Spartan run of Pajero and Montero (and Shogun) SUVs sold worldwide involves significant revisions to the suspension in order to cope with racing through the African desert. Mitsubishi raced first-gen Pajeros before developing the Evo proper, which received different unequal-length A-arms and coilovers for the independent front suspension versus a standard version while simultaneously ditching Pajero’s traditional solid rear axle in favor of independent rear suspension. Looking back, the layout blurs the lines between Gen 2 and 3 Monteros, though, unlike the Evo, the Gen 3 switched to a unibody rather than a body-on-frame chassis.

I noticed one of the most impressive parts about that suspension system the first time I got my Evo up on a lift, as the front wheels and tires drooped down and outward rather than swinging inward. Ideal for catching air and nailing landings, obviously, just like those vertical stabilizers. Of course, in a similar fashion to the more well-known Lancer Evolution compact sports sedan, the Pajero also uses a much more powerful engine—though not by bolting on a turbocharger, something of a bummer but a detail which I hope should help to improve reliability and longevity of my high-mileage truck.

Instead, the Evo’s 3.5-liter dual-overhead-cam V6 uses some components from the second-gen SR engine, with an early application of Mitsubishi’s MIVEC valve timing system for the heads. Think VTEC, VANOS, or VarioCam, but the resulting peak of 276 horsepower during the Japanese automaker “Gentlemen’s Agreement” definitely feels underrated once the Evo comes onto that second cam at about 5,000 RPM.

Meanwhile, the Gen-2 Montero’s Aisin three-speed automatic with overdrive went out the window in favor of a new five-speed automatic. The factory offered a stick shift, though I believe the Dakar race trucks actually used a manual gearbox built by Holinger in Australia for V8 Supercars. That Aisin trans appeared later in the Gen-3 Montero, but desert racing in the Evo’s dictating shorter gear ratios and a reprogrammed TCM that holds gears higher into the rev range.

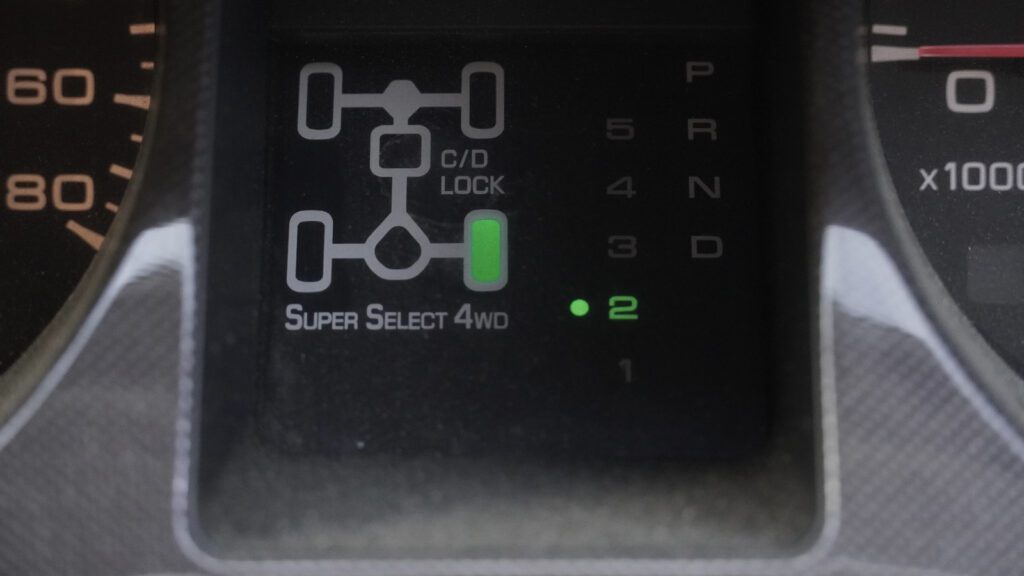

The four-wheel-drive transfer case also resembles a Montero’s, with a similar Super Select gear lever that allows for shifting between 2-Hi and 4-Hi on the fly to produce all-wheel drive, as well as locking the viscous center differential for more traditional four-wheel drive. Switching to 4-Lo requires coming to a stop in Neutral, though the live axle trucks’ optional rear locker gives way to Torsen automatic torque biasing front and rear differentials on the Evo.

On the interior, the racecar theme continues with unique Recaro seats—most similar to an Isuzu VehiCROSS, actually, but with adjustable bolsters and different cloth upholstery. The Evo, therefore, rides tighter and higher than a Gen 2 Montero, allowing for better visibility over the hood. Almost every Evo needs repairs to the cloth bolsters from drivers and passengers sliding up and into the seats, though, and that cloth also attracts dog hair better than velvet, even though I’ve only allowed the dog in the car twice ever.

A nice set of original front floor mats features a rubber inset to collect dirt and pebbles while off-roading. Other fun details include carbon fiber trim to distinguish the Evo’s dash from more pedestrian and otherwise identical Pajero dashes. That carbon fiber optionally extended to the tall gearshift lever, which allows for bang-shifting using an early Tiptronic-style selection, with Up towards the front and Down towards the back (the inverse of a present-day sports car’s automatic or a racecar’s sequential). My truck came in relative poverty spec, though, and I do wish I could find a few of the dealer options like front light pods, a ski rack, and an aluminum fuel filler door.

The biggest bummer? Probably that no Evo has cruise control. Because racecar, duh.

Keeping a Mitsubishi stock? Surely not…

The obscure Dakar legend of a short-wheelbase, cartoonified racing truck helps to explain why anyone who knows about the Pajero Evo gets absolutely stoked to see one. I bought the truck to share with the Montero community—which partially explains why I chose an automatic, too—and have met many other owners both online and in person so that we can coordinate parts sourcing and modifications.

I plan to keep my PajEvo as close to stock as possible, other than swapping on a three-spoke OEM steering wheel from a Mitsubishi Eclipse to replace the delaminating rim on a surprisingly bland four-spoke that matches an otherwise standard Montero. And I just love a three-spoke steering wheel anyway.

My Evo also arrived with tired Yokohama HT street tires that aren’t even sold here in the States, so I swapped on a set of incrementally taller Geolandar A/T rubber that might better take the beatings I planned to dish out in the dirt. While chatting with some of Yokohama’s engineers at Nitro Rallycross last year, I learned that any of the historical photos I found of Dakar race trucks wearing Yokohama tires probably showed privateer teams. Mitsu’s factory trucks only used BFG and Michelin, apparently.

So far, those Geolandars have held up quite well, both on-road and off. About 5,000 kilometers in, the front shoulders already show a bit of wear, which I attribute to my penchant for ripping this body-on-frame truck faster than most Porsche 911 or Ferrari owners up in Malibu—but I figure that’s to be expected while driving high-sidewall LT-metric truck tires mounted on a high-powered 4,300-pound vehicle anyway. At highway speeds, the tires barely peep. (No, I haven’t found any snow yet, sorry.)

I also swapped out the flimsy steel underbody panel for true skid plates built by Adventure Driven Design. In fact, the OEM piece looked more sturdy than the typical plastic used by most manufacturers these days, but thicker aluminum should hopefully prevent any flying pebbles from damaging unobtanium parts under there. Again, the similarities to Monteros helped here since only one little tab on a Gen 2’s transmission skid needed trimming to fit the Evo’s revised control arm mounting location. After my guinea pig experimentation, I sent the correct measurements to Adventure Driven Design, so the site now sells perfect Evo skid kits online, along with a host of other Montero and Pajero parts.

Aftermarket parts support for Monteros and Pajeros from companies like ADD, in general, makes up a tiny sliver of the off-roading industry here in the United States. However, the passionate community relies heavily on international suppliers who stockpiled OEM parts before Mitsubishi’s steady decline left everyone in the lurch. For both the Monteros and the Pajero Evo, I regularly order everything from suspension components to oil cooler lines from Partsouq in Dubai, and shipping isn’t even too terrible.

I’ve also struggled to get mixed results with the incredibly frustrating order systems of Amayama and Nengun Performance out of Japan. I just took a quick gamble on some front upper ball joints from Megazip that actually arrived fairly promptly. But availability for the Evo specifically depends partly on the fact that Mitsu never actually built much in the way of spare parts, so a number of companies in Australia and Europe also cater to custom requirements. My replica aluminum side steps came from Paves Garage down under, while EVO Shop GmbH (in Switzerland, I believe) has sent me a few targeted ads on IG for bushings, brake lines, and other components—priced just high enough to tempt me if a fit of desperation hits.

Sorting out the little details

A little detail that I learned quickly about bringing a JDM car to the United States required much longer to solve than expected: it turns out that AM and FM radio frequencies vary across the Pacific. And my OEM radio, which previous owner(s) clearly never bothered to replace, only made bad noises through what sounded like blown-out speakers. I tried a cassette adaptor, tried swapping in my Montero’s original radio, and even tried to splice in a Bluetooth adaptor through the empty CD changer port.

Eventually, I broke down and bought a retro-styled VDO Continental aftermarket head unit that almost, but doesn’t quite, match the rest of the Pajero’s blue-green dash lights. The head unit allows for Bluetooth, my main requirement, but not dimming of the screen or button bulbs—so I put a thin dimmer film on the screen to prevent nighttime glare. All this to avoid a double-DIN screen low down in the dash, so that I can keep the so-damn-Japanese felt-lined sunglasses drawer and pull-out cupholders.

Another “because racecar” moment arrived when I discovered that the Pajero Evo lacks door speakers, despite the standard Pajero front door cards, which do have speaker panels built in. So I broke down again and bought Pioneer four-inch dash speakers in the hopes of gaining a bit of audio crispness with minimal effort involved (pulling the 6×9 rear speakers will eventually happen, but it requires popping off almost all of the rear interior paneling).

A fellow PajEvo owner also came to the rescue in a big way quite recently when he sent me instructions for how to reprogram the OEM key fob that came with my car but seemed not to work despite its little red bulb flashing and a battery replacement. I won’t share the exact details of how to reprogram the fob because it was literally so easy that I’m now scared to park the Evo anywhere even remotely sketchy and plan to wire in a hidden kill switch (and almost certainly invest in The Club as an additional visual deterrent, too). But the simple act of locking and unlocking without needing to slide a key into a tumbler makes the Evo feel so much more modern.

[Button id=”410″]

Keeping the Dakar dream alive

Meanwhile, I installed a set of phone and camera mounts from Bulletpoint Mounting Solutions on the original dashtop gauge cluster to hold my phone in place of a double-DIN screen (don’t worry, I found a replacement gauge cover to drill into). And I slid an Element fire extinguisher into the little retaining clip that originally housed a by-now-missing flare in the passenger footwell. Similar other details point to Mitsubishi’s incredible attention to detail during the 1990s, from the rear door toolkit’s easy access and useful selection to the rear wiper’s pour funnel that prevents messes while refilling fluid.

I want to keep the original Japanese stickers on the windows as long as possible, but I did add a few warning stickers from my time in Saudi Arabia at the 2023 Dakar Rally on the driver’s side sun visor. And even if an Optima Yellowtop stands out like a sore thumb in the engine bay, I figure a better battery makes sense given my travel schedule—no matter how much I daily drive the Evo while at home, I’m still not home nearly enough.

In terms of maintenance, after getting the engine and trans running without leaks, my main focus lately has been refreshing the front steering and suspension. Again, most steering components drop right in from a Gen-2 Montero, including the tie rod ends, idler and pitman arms, and steering box (the latter with a tighter ratio, though). Swapping in new pieces for all of the above, plus upper front ball joints, already made a huge difference in tightening up some of the vague play that I formerly attributed to the truck-ness of the Pajero Evo (and I’ve got a story on that, too).

Just don’t ask how many pullers I needed to actually get the pitman arm off or how much the penetrating oil costs. I still need to pull the hubs to replace the front lower ball joints and maybe a CV boot that I tore in the process of struggling without having the right tools in the past. The Evo, unfortunately, also seems to suffer from the same degraded “redball” transfer case shifter as Gen-2.5 Monteros. Luckily, I have a spare “whiteball” shifter sitting around, but I need a hydraulic press to swap it into the Evo’s shift lever, which bends in the opposite direction compared to an LHD Montero. Then, with a few dash bulbs replaced for the 4WD and gear selection gauges, I should be all set with my (current) to-do list.

But other maintenance items have left me in the lurch. The entire rear suspension uses ball joints and bushings that come built into the arms—more unobtanium. I want to do a valve cover gasket job to stop some slight oil seepage, but I can’t find the wasted spark plugs’ wires with the correct size tubes to fit the taller MIVEC heads. Should I wait and hope to find either OEM or aftermarket parts, or just try to cobble a solution together? A bit of Mickey Mouse mechanical skill already fixed a clunking and squeaking rear door latch, after all, requiring more than a few hours spent fiddling with seals and striker plates and rear cargo area lighting.

So yes, owning a high-mileage Pajero Evolution ends up testing the concept of a labor of love. But I never thought I’d be able to check off owning my third-favorite car of all time by the age of 35 (behind a Lancia Stratos and Porsche 959, no less). And I truly chuckle every single time I see the PajEvo, not to mention every time I rip up a canyon in Malibu or along a dirt track out in the desert.

Daily driving an RHD JDM legend isn’t even all too bad in traffic, and it has inspired me to keep an eye out for a few others on the off chance I can scrounge up a bit more cash. But in the meantime, I keep reminding myself how lucky I truly am to have taken a leap of faith and imported this homologation special from Japan. So to all those would-be JDM enthusiasts out there, if you happen to see a guy grinning ear to ear from the wrong side of the road in a Pajero Evolution, rest assured that with a little bit of luck (and maybe a lotta bit of) elbow grease), you too might one day soon live out the same dream.