It happens to the best of us. You’re driving on a rural road, not a streetlight for miles, blissed out on the solitary joy of motoring. Next thing you know, you’re blinded by the cool white light of an F-150’s high beams. “How rude,” you think, as the brightest LED headlights you’ve ever seen burn your retinas. Little psychedelic spots start pulsing in your field of vision. “Headlights are too bright,“ you exclaim. And you’re absolutely right. Relief from nighttime driving glare is coming in the form of adaptive headlight systems, but it could take a while.

How did we get here?

The first electric vehicle headlamps were manufactured by the Electric Vehicle Company of Hartford, Connecticut for their Columbia Electric Car (seen here with C.S. Rolls of Rolls Royce riding shotgun) in 1898. The lamps used filaments and dynamos in an adaptation of Edison’s incandescent bulbs which had only been invented 19 years prior.

In 1915, the Guide Lamp Company (later a part of General Motors) developed the first dimmable headlamps. This innovation reduced nighttime driving glare by “dipping” the bulbs, but the lights had to be manually adjusted from outside the vehicle. Levers and foot switches were later developed to “dip” or change the angle of the bulbs or lenses. The next few decades saw the development of the “sealed beam” headlamp, with a parabolic reflector, filament, and plastic or glass lens all sealed into one unit.

In 1940, a consortium of US state motor vehicle administrators created a rule mandating that all vehicles sold in America have round 7″ headlamps like the ones seen on this Ford Coupe. High and Low Beam technology continued to advance, with Cadillac introducing its “Autronic Eye” system in 1954. This early example of adaptive headlights could automatically dim the lights when another vehicle is approaching. Or so it was supposed to.

It was a humorously rudimentary system that operated off whatever a dash-mounted phototube detected. Street lights reportedly set it off, but it was hilariously bad at detecting oncoming cars, the one thing it was supposed to account for. And in corners with the narrow-focused phototube staring straight off at nowhere? Forget about it. But hey. A for effort. OEMs continued developing such devices over the years, later trickling to Ford, Mercury, and Lincoln, but their complexity and serviceability at the time limited their appeal.

Around the world, halogen bulbs were being developed by European carmakers in 1962, allowing high beam intensity of up to 140,000 candelas, a measurement of light intensity that roughly translates to “how many candles bright is this.” No, seriously. American automakers balked, calling the halogen headlights too bright and eventually settling on a limit of 75,000 candelas. Halogens would remain the industry standard until LED headlights were introduced in the 2010s.

Over the next few decades, the rules would change multiple times. Rectangular headlamps got the thumbs up in 1974, paving the way for iconic car designs like this 1975 Cadillac Coupe Deville. In 1983, the consortium finally allowed for replaceable bulb headlights, finally making the process of replacing a burnt-out headlamp as easy as, well, changing a lightbulb.

But how you’re still asking, did we end up with the brightest LED headlights assaulting our rods and cones when all we want to do is enjoy the simple pleasure of moody nighttime driving while listening to synthwave? Well, put on your nerd glasses because we’re gonna learn about the history of LEDs.

How did Blue LEDs change the world?

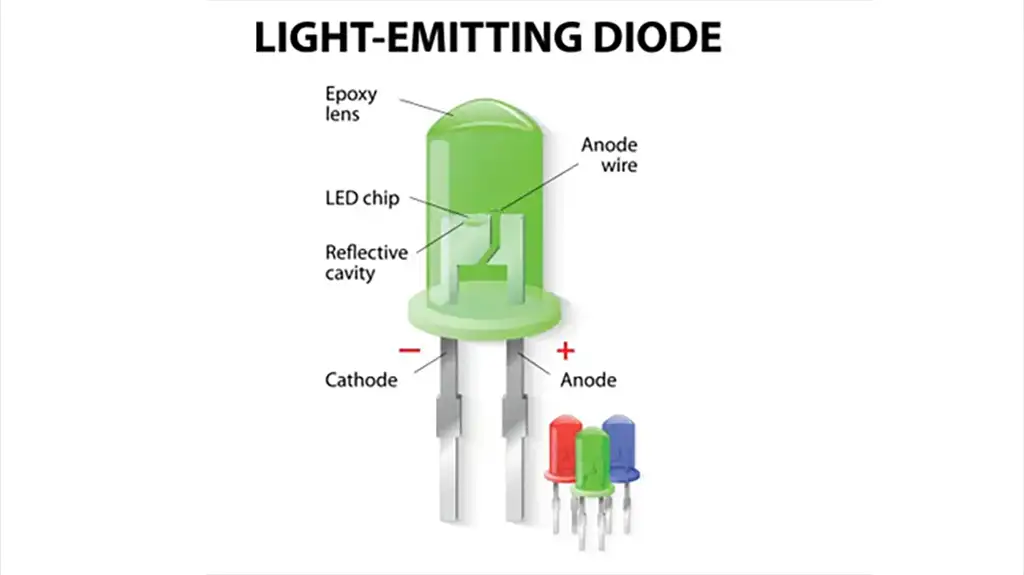

To understand how white LEDs became so ubiquitous, we should take a quick trip through the history of LEDs themselves. Light Emitting Diodes, or LEDs in case you weren’t paying attention, are far simpler than incandescent bulbs. The LGR Tech Tales video above explains it better than I ever can.

Because of this simplicity, LEDs are everywhere, from toys and electronics to cars and motorcycles, and even the silly RBG light strip beneath the neighbor kid’s clapped-out Hyundai Elantra.

Rather than requiring a sealed bulb and dynamos that arc electricity across a filament, LEDs are basically a piece of wire enclosed in a lens-shaped translucent resin or epoxy that glows a specific color when a current passes through it. Modern LEDs are a little more complex, but the main operating principle remains the same: get the most light from the least energy. This means that LEDs, when used correctly, will draw far less energy while lasting much longer than traditional incandescents.

The resin being used determines the color of the LED, similar to how fireworks’ colors come from the chemicals or compounds in the rocket. Scientists were able to develop red, green, and yellow LEDs, all of which became fairly common in 1970s and 1980s electronic devices, with red LEDs even powering the lasers that made CDs possible. But for decades, one color that would unlock the full visible spectrum eluded engineers — blue.

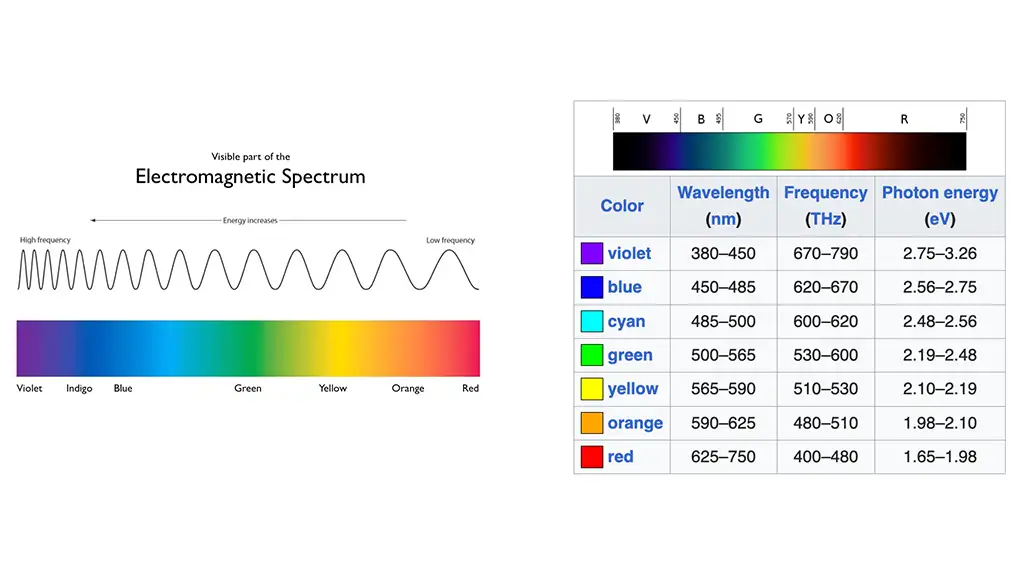

Blue LEDs were hard to make for a couple of reasons. First of all, to produce the blue hue, the resin needed to be made with Gallium Nitride, which was expensive to manufacture. Most importantly, because of the nuances of the electromagnetic spectrum, blue (and violet) light requires considerably more energy to produce a viable amount of light, effectively canceling out the benefits of using LEDs to begin with.

Why does this even matter, we’re supposed to be talking about white LEDs aren’t we?

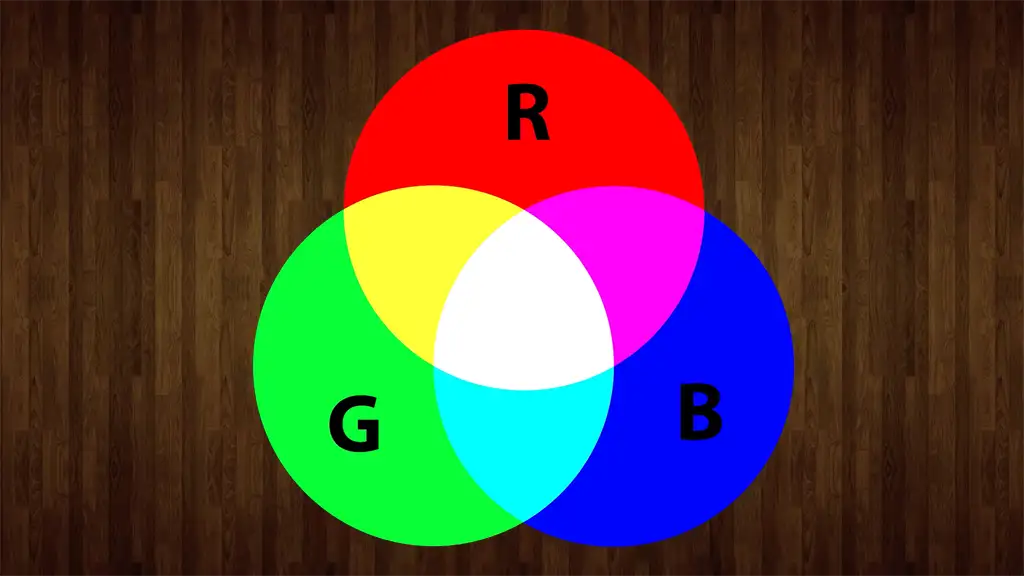

Turns out that in the visible light spectrum, colors don’t work the way they do with arts & crafts. As you can see here, red and green combine to make yellow, blue and green combine to make cyan, red and blue combine to make magenta, and right there at the heart of the Venn diagram, pure white light — containing the full spectrum of visible color.

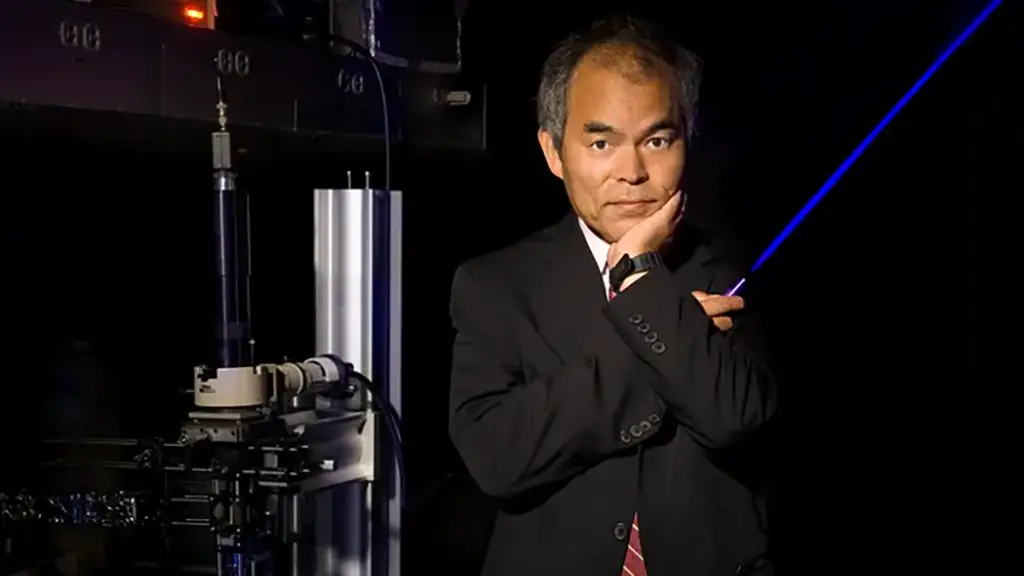

It wasn’t until 1993 that the first viable Blue LEDs were produced, but once they were, tech companies were off to the races. The new high-frequency beams enabled the enhanced data storage that brought us Blu-Ray discs and modern disc-based gaming systems. The inventors of Blue LEDs even received the Nobel Prize in 2014.

Most importantly to our story, this advancement enabled the production of the white LEDs that have changed the world… And made headlights too damn bright.

Why are headlights so bright now?

How did we get to a point where 50,000 people have signed a Change.org petition calling for banning LED headlights? But why exactly are these diodes wreaking such havoc on our night vision? Put simply, the efficiency and relative brightness of the LEDs, paired with the cooler blue (rather than the warm orange of halogens) cause, “significantly stronger discomfort reactions,” according to Daniel Stern, chief editor of Driving Vision News, in an interview with the New York Times. Pair this natural discomfort with the size incongruity as our pickup trucks get more massive and our sports cars get closer to the ground and you’ve got a perfect storm of glare-inducing light.

I asked Clint from LGR if he had any thoughts on LED headlights and their increased ubiquity since his YouTube essay was published. Here’s what he said (for best effect read this in an approachable, soothing tone):

LED headlights are as distracting and dangerous as ever – when badly implemented. I do approve of the use of white LED strips *around* headlights that I see more often now, especially for daytime running lights. I also can’t wait to see more of those smart adaptive LED headlights that dim parts of the light to prevent blinding passing drivers, although US regulations have been really slow to get that off the ground here.

Clint Basinger – LGR

What are adaptive headlights, and why don’t we have them here?

Within a decade of white LEDs being available, studies were already being conducted to figure out if they were too bright for use as vehicle headlamps. 2005 research by Newel Stephens and Albert Bolander found “that lamps with multiple bright and dark areas, such as LED lamps, were generally perceived to be brighter than a standard incandescent lamp with a more evenly illuminated lens.”

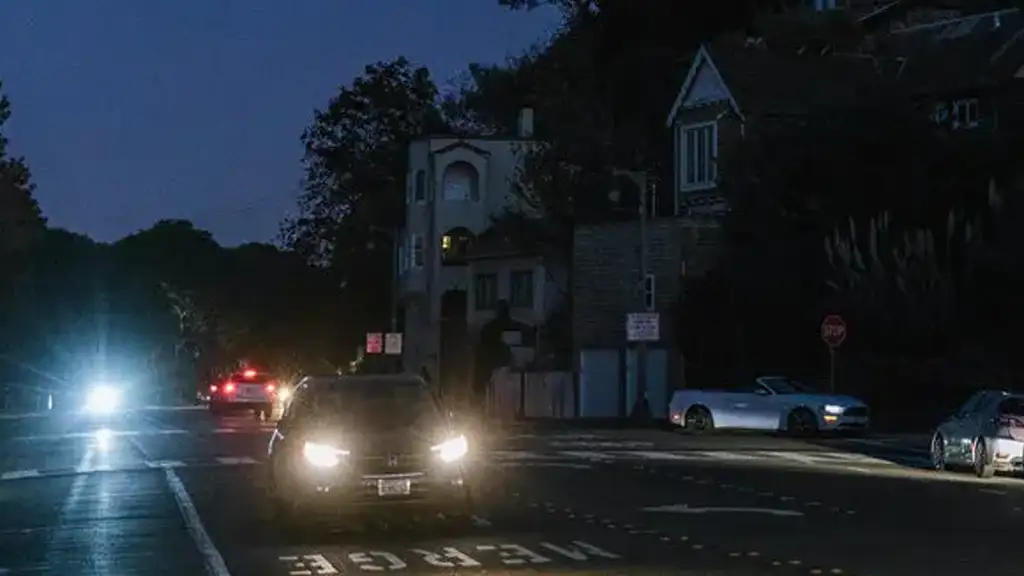

Here’s a pretty good illustration of the stark difference between the halos visible with halogen bulbs (on the Honda in the foreground) and whatever LED glare monster is approaching from the background.

As LED headlights started to become more en vogue, European carmakers developed automated adaptive headlight systems to mitigate the effects of road glare — with the technology becoming standard as early as 2012. Due to regulatory quirks, American cars had to operate with a strict high beam/low beam binary until the rules were relaxed in 2022.

We must also note that adaptive headlights differ in this context from the auto-dimming and auto high-beam lights first drafted in ancient American cars. Yes, we have plenty of cars nowadays capable of dimming the lights at the site of oncoming traffic, but there are very few that are truly adaptive. But adaptive how, exactly?

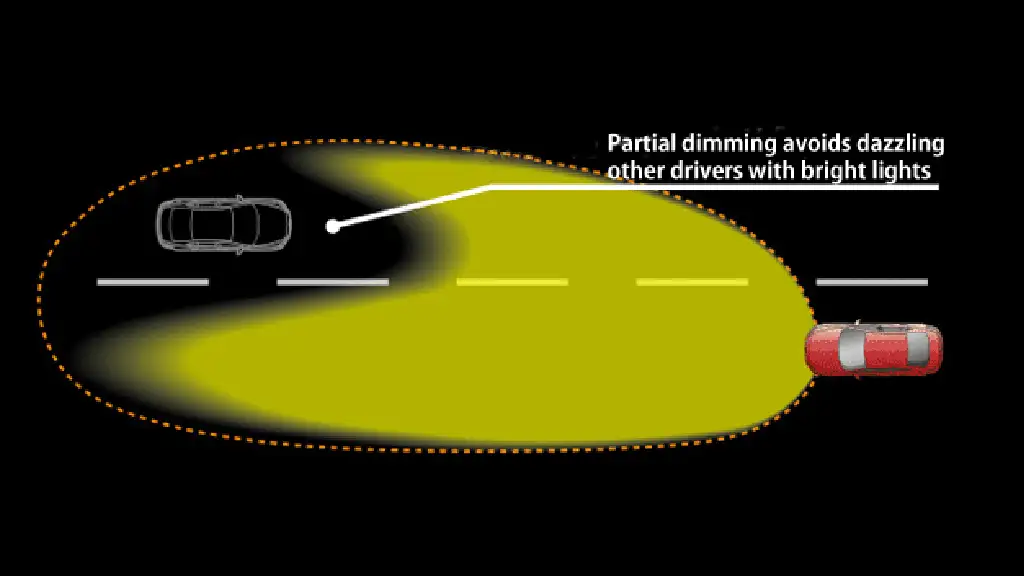

While technically, “adaptive headlights” have been around since Cadillac’s Autonic Eye, eyeball-searing LED headlights can be mitigated with what’s called adaptive beam technology. As demonstrated in this Mazda illustration, this works by dimming the LEDs that could create glare for oncoming drivers, allowing them to pass without catching a face full of that razzle-dazzle.

Automakers and drivers alike have been frustrated by regulators dragging their feet on the change, as Audi’s senior vice president of product management told NBC News earlier this year: “For the U.S. specifically, we have well over 150,000 cars on the road today that could have it if we just turn it on. … The capability is already there.”

The regulatory change that brought adaptive beam headlights Stateside was, confusingly enough, part of the 2021 Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (H.R.3684). Enshrined in law alongside keeping our bridges and tunnels from falling down is Section 24212, which inserts the research and development of adaptive beam headlights into the high beam/low beam binary regulations. According to a New York Times article from when H.R. 3684 became law the following February, the new adaptive beam headlights are still beholden to the 75,000-candela limit established in the 60s and 70s.

Automakers are scrambling to update their vehicles with the technology, including GMC who recently had to recall 740,581 of their 2010-2017 Terrain SUV models for violating headlight brightness standards. Hopefully, the next generation of LED headlights will have a better fix than what GMC did to remedy this issue, a “Headlamp Applique Kit” which can charitably be called “slapping some frosted stickers on the lens.”

So we just have to sit and wait?

Unfortunately, carmakers are not moving away from ultra-bright, ultra-efficient LED headlights any time soon, but why would they? When adaptive beam technology becomes standard or at least more ubiquitous on American roads, we’ll hopefully see considerably less nighttime driving glare. Adaptive headlights will especially cut down on the effect of headlights that are too bright due to vehicles with higher ground clearances, like today’s full-size pickups and maxed-out SUVs. By then, perhaps the German’s laser lights will seem far less egregious.

Until then, there are some steps you can take to reduce nighttime driving glare, according to Visionworks:

- Get your eyes checked: Common vision problems like astigmatism can cause “halos” to appear around bright lights at night. If halos have worsened considerably of late, you may be experiencing a more urgent issue with your vision as well.

- Keep your glasses and windshield clean: Windex is your friend. Keep a bottle in your car along with some paper towels and keep your windshield as clean as possible, on the inside and outside.

- Dim your dashboard lights: The brightness of your console could be causing additional strain on your eyes as you drive. The aforementioned deal with blue light is also why more modern cars are including nighttime screen modes or screen-off switches to lessen the strain during your Ryan Gosling Drive mood swings.

- Don’t buy those blue-blocker glasses that claim to enhance your night vision: Originally developed for hunting and fishing, because the yellow lens makes objects stand out against the blue of the sky or water, these glasses do not help you drive at night. Even worse, some studies have shown that they make it harder to see pedestrians on the road at night.

- Consider glare-reducing lenses: There are, however, lenses coated with layers of specific oxides that can help reduce glare. You don’t need to wear glasses full-time to get these, as they’re similar to glasses that have been marketed for computer eye-strain reduction.

These methods will help you drive at night with considerably less eye strain, but they pale in comparison to the impact of true adaptive beam headlamp systems. Soon, Americans will know the happiness that comes with not being blinded by the brightest LED headlights ever made.

Until then, we can all agree: Headlights are too bright!